The question sounds absurd on its face, the kind of provocation designed more for cable news chyrons than courtrooms. But after days of escalating rhetoric from the Trump administration, its allies, and the Justice Department itself, the idea no longer feels theoretical.

Could Don Lemon actually face criminal charges for covering a protest?

That is the implication left hanging after Assistant Attorney General Harmeet Dhillon publicly accused Lemon of participating in a “criminal conspiracy” for reporting on an anti-ICE protest that briefly disrupted a Sunday church service in St. Paul, Minnesota. Dhillon’s comments, delivered on conservative influencer Benny Johnson’s podcast and amplified across right-wing media, framed Lemon not as a journalist documenting civil unrest, but as an embedded actor in it.

“Nobody should think in the United States that they’re going to be able to get away with this,” Dhillon said, vowing that the “fullest force of the federal government” would come down on protesters. While she stopped short of explicitly confirming charges against Lemon, she named him repeatedly, questioned his intent, and dismissed journalism as a shield against prosecution.

The effect was unmistakable. Lemon was placed “on notice.”

The confrontation began Sunday when activists protesting Immigration and Customs Enforcement entered Cities Church in St. Paul during a worship service. The demonstrators were responding to the killing of Renee Nicole Good, a Minnesota woman shot and killed earlier this month by ICE officer Jonathan Ross during an immigration enforcement operation. The Trump administration has insisted Ross acted in self-defense, a claim disputed by protesters and some local officials who cite video footage showing Good attempting to drive away.

Lemon was present as an independent journalist, livestreaming and interviewing protesters, congregants, and a pastor who ultimately asked him to leave unless he was there to worship. At multiple points in the footage, Lemon explicitly stated that he was not affiliated with the activists and was present solely to report.

“This is what the First Amendment is about,” Lemon said during the livestream. “The freedom to protest.”

That distinction did not matter to Dhillon.

In her remarks, Dhillon argued that Lemon had prior knowledge of the protest and therefore could not claim journalistic neutrality. She suggested that by entering the church and continuing to film, Lemon crossed the line from observer to participant.

“Committing journalism’ is not a shield,” she said, accusing him of being an “embedded part” of criminal conduct.

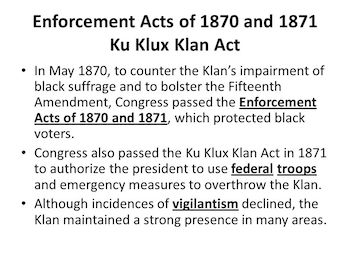

The Justice Department later confirmed it was investigating potential violations of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, known as the FACE Act, as well as the Enforcement Act of 1871, more commonly referred to as the Ku Klux Klan Act.

The pairing of those laws and the target of the rhetoric has raised alarm among press freedom advocates and civil rights attorneys.

The FACE Act was enacted in 1994 in response to escalating violence and obstruction at abortion clinics. It makes it a federal crime to use force, threats, or physical obstruction to interfere with people seeking reproductive health services. The law also extends protections to religious worship, prohibiting interference with people exercising their faith inside houses of worship.

Civil penalties and criminal charges under the FACE Act have historically been used against protesters who block clinic entrances, chain themselves to doors, or threaten providers and patients. Applying it to journalists covering a protest, particularly one who did not organize or lead the disruption, would represent a significant expansion of its scope.

Legal experts note that while protesters inside the church could face trespassing or disorderly conduct charges under state law, invoking the FACE Act against a reporter would be highly unusual and constitutionally fraught.

Even more jarring was Dhillon’s invocation of the Enforcement Act of 1871, a Reconstruction-era statute passed to combat white supremacist violence and protect the civil rights of newly freed Black Americans.

The law allows federal authorities to prosecute conspiracies to deprive individuals of their constitutional rights, particularly when state governments refuse or fail to act. It was designed to dismantle the terror campaigns of the Ku Klux Klan, not to police journalists livestreaming protests.

Yet Dhillon suggested the statute could apply whenever people “conspire” to violate protected civil rights, implying that disrupting a church service could qualify.

For many observers, the symbolism was impossible to ignore; a law born out of Black resistance to racial terror is now being floated against a Black journalist for documenting state violence.

Lemon has said the framing itself is revealing.

“It’s notable that I’ve been cast as the face of a protest I was covering as a journalist, especially since I wasn’t the only reporter there,” he said in a statement. “That framing is telling.”

What followed was even more telling. Lemon said he has received a barrage of violent threats, homophobic slurs, and racist attacks online, much of it amplified by right-wing media figures and political allies of President Donald Trump.

Trump himself weighed in on Truth Social, calling the protest a “church raid” carried out by “agitators and insurrectionists” and suggesting they should be jailed or deported. He also called for investigations into Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and Rep. Ilhan Omar, both Democrats who have opposed ICE enforcement actions.

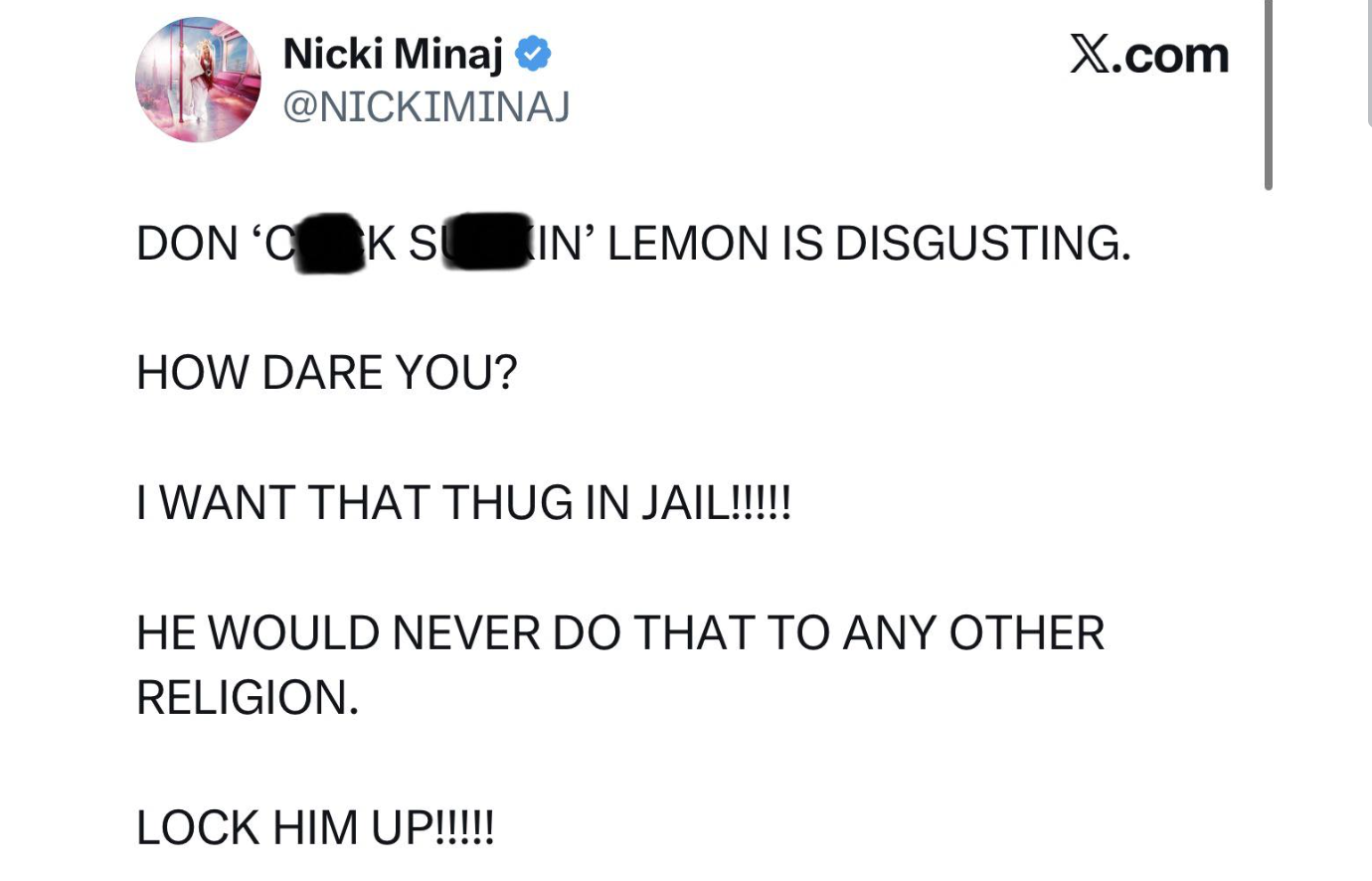

The president’s allies went further. Rapper Nicki Minaj used a homophobic slur to call Lemon “disgusting” and demanded he be locked up, later claiming she used the language deliberately to draw attention. Lemon dismissed her remarks, saying she did not understand journalism and was speaking beyond her capacity.

The convergence of government threats, celebrity pile-ons, and online harassment has transformed a local protest into a national spectacle.

There is something deeply off about watching the machinery of federal power train itself on a Black, gay journalist under the banner of “law and order,” particularly when the underlying issue is a killing by federal immigration authorities.

Lemon has repeatedly pointed out that the outrage directed at him far exceeds the attention paid to Good’s death.

“If this much time and energy is going to be spent manufacturing outrage,” he said, “it would be far better used investigating the tragic death of Renee Nicole Good, the very issue that brought people into the streets in the first place.”

Instead, the narrative has shifted. The question is no longer about ICE accountability or the use of lethal force. It is about whether journalism itself can be criminalized when it becomes inconvenient.

Press freedom advocates warn that even without charges, the threat alone is damaging.

When a Justice Department official publicly suggests that reporting could be evidence of conspiracy, it sends a signal to journalists, particularly freelancers and independent reporters without institutional backing. Cover this, and you could be next.

It also raises questions about selective enforcement. Churches have been disrupted by protests across the political spectrum for decades, from antiwar demonstrations to climate actions to anti-abortion campaigns. Rarely has federal law enforcement responded by threatening Reconstruction-era prosecutions.

That this moment centers on immigration, race, and queerness is not incidental. It fits a broader pattern of using the language of law to discipline dissent while insulating state violence from scrutiny.

As of now, no charges have been filed against Lemon. Legal experts say prosecuting him under the FACE Act or the Ku Klux Klan Act would face steep constitutional hurdles, particularly given his repeated statements that he was not participating in the protest.

But the point may not be conviction; it may be intimidation.

By placing Lemon “on notice,” the administration has already achieved something; it has shifted the terrain, reframing journalism as suspect and protest coverage as dangerous. It has reminded reporters that proximity to dissent can be rebranded as complicity.

Whether or not Don Lemon ever sees the inside of a courtroom, the message has been delivered.

And that, perhaps, is the most unsettling answer of all.