Earlier this year, Snoop sparked backlash after an episode of the It’s Giving podcast, where he admitted that while watching the movie Lightyear with his grandson, he felt unprepared to explain a lesbian couple featured in the film. He recalled:

“It’s like, I’m scared to go to the movies now. Y’all throwing me in the middle of sh-t that I don’t have an answer for.”

He added: “They’re going to ask questions…I don’t have the answer.” Those remarks came on the heels of global cultural shifts in how queer families and queer lives are depicted.

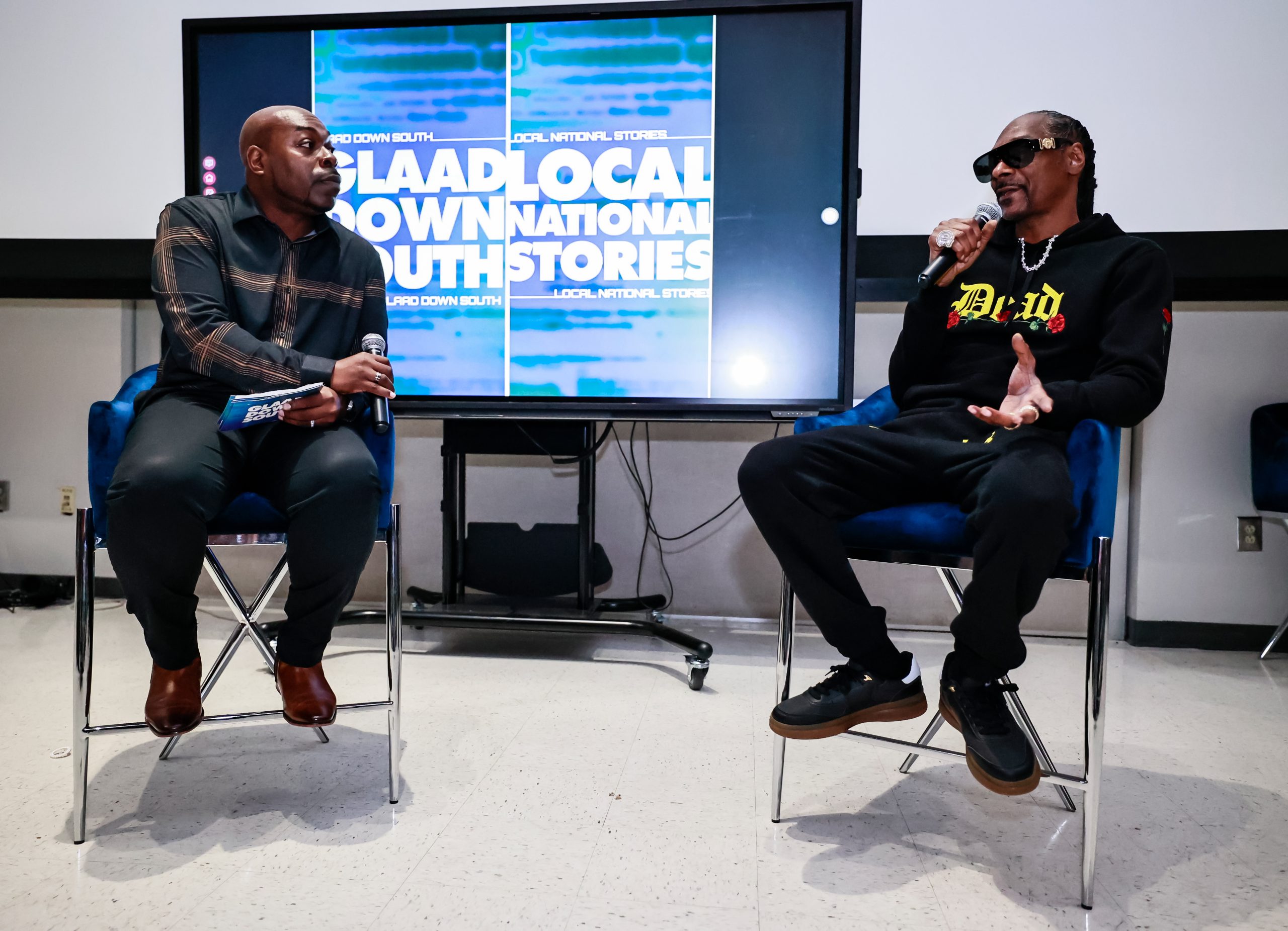

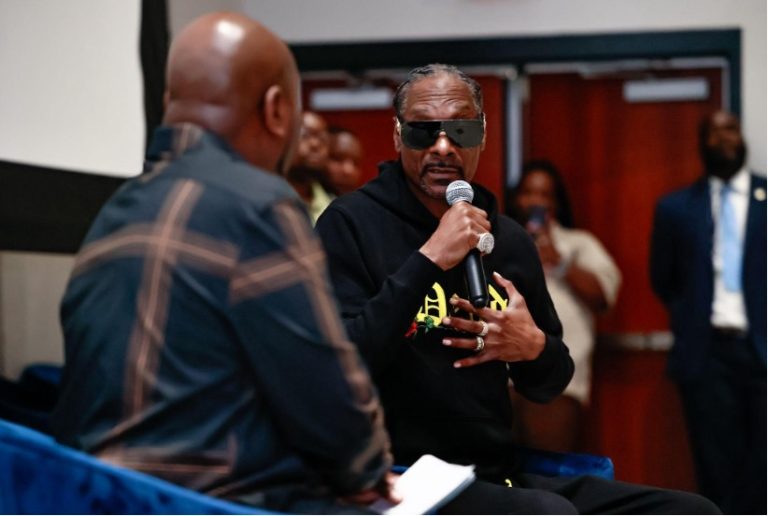

During the GLAAD fireside chat with Darian Aaron (GLAAD Director of Local News: US South), Snoop reflected on his own ignorance:

“I’ve always advocated peace and love and diversity. I had no understanding of a situation that was brought before me while I was with my grandson. But through time and experience and love, you learn to live and you get information, you find out how to understand things better. I have friends that are same-sex parents…” “And then if you think back to the Olympics, they don’t give that torch to nobody that doesn’t represent peace. So when they put that in my hand, that means I’m a peace messenger…”.

“What I did with this particular piece in Doggyland, we dealt with parents that probably don’t look like a parent you would expect, its parents that are sometimes same-sex parents or parents that are different races or whatnot, but the key is love, and that’s what the key was with the song that we did – was to push love and let people know that when its dealing with kids and parents, the main issue is love because a lot of parents grew up with a mother and father but didn’t get no love.”

Snoop Dogg continued, “It’s about the parent giving that baby or giving that kid love and if that parent is same-sex, different religion, different race or whatnot, that’s not the key, the key is love that is being pushed into that baby so that baby can grow up with love in their heart.”

His reflection comes shortly after him publicly backing same-sex parenting on Spirit Day, a day to advocate for anti-bullying against LGBT youth, stating: “It’s a beautiful thing that kids can have parents from all walks [of life], and be able to be shown love… whether it be two fathers, two mothers, whatever it is, love is the key.”

These admissions hint at a transformation. Yet they also reflect a backward glance into territory where questions of discomfort were left unchallenged for far too long.

The world has changed since Snoop’s rise in the ’90s. Queer visibility, family diversity, inclusive storytelling these are no longer side notes, but core. His discomfort, “I don’t have the answer,” reveals a blind-spot that many in the Black community, especially heterosexual men from a particular era, share. But we can’t leave it alone. Representation matters because it shapes how children see families, how youth see themselves, and how communities learn or fail to learn compassion.

Snoop’s recent music collaboration with GLAAD, his children’s show “Doggyland,” and his stated support for same-sex parents suggest movement. Yet the rhythm of hip-hop’s past, its homophobic slurs, coded exclusions, macho-postures, still echoes. So when Snoop says, “The key is love… what I did with this particular piece is I dealt with the parents… whether it’s same-sex parents… the key is love,” we should listen, but also ask, what’s next?

Here’s where we must pause and tell the harder truth, the unease with queerness in parts of the Black community often isn’t born of hate, but of inheritance, handed down like superstition, tucked between Sunday sermons and locker room jokes. Internalized homophobia doesn’t always arrive as cruelty; it often shows up as silence, as side-eyes, as the refusal to name love when it doesn’t look familiar. It lives in our language, our pulpits, our “I just don’t understand” disclaimers that masquerade as innocence but wound just the same.

Snoop’s “scared to go to the movies” wasn’t just a generational slip, it was a symptom of that inherited fear, the confusion of someone confronting a world that no longer lets ignorance hide behind nostalgia. But if we only cancel him, we miss the point. Liberation demands more than punishment, it demands transformation.

To move forward, we must do what the tradition of Black radical love has always done, hold our people accountable without exiling them. That means giving grace while still expecting growth. It means saying, “We understand where you came from, but you can’t stay there.” It means teaching our elders and peers the language of inclusion the same way they taught us the language of survival.

Liberation asks us to love each other enough to interrupt the harm. To sit with discomfort long enough for it to become understanding. To turn ignorance into inquiry, and inquiry into solidarity.

Because love, by itself, is not enough. Liberatory love is love that studies, apologizes, repairs, and relearns. It is the kind of love that looks at a statement like Snoop’s and says: I see the boy who was once afraid, but I need the man to do better.

That is the grace, accountability, and that is how we build a future where queerness is not tolerated, but celebrated, as an inheritance, not a debate.

In a night stitched with intention, part education, part atonement, Snoop Dogg seemed to reclaim a fragment of his legacy, or at least gesture toward repair. Yet this moment was never meant to be a coronation. It was a checkpoint. One that tested whether growth can survive the weight of history, or whether apology can coexist with influence.

On campus, Snoop’s appearance wasn’t just symbolic, it mattered. In front of students, health-advocates and HIV prevention specialists from the U.S. South joined the dialogue, reinforcing that HIV is not a relic of the past, that stigma still lives, and that representation and education matter deeply. Snoop stepped into this cultural tightrope, acknowledging his mis-steps while aligning with a vision of inclusion. He said: “There was no medical information to let us know what was going on. We were so scared, we stopped everything.”

“How do you treat it [HIV]? How do you prevent it?…Hopefully, in 2025, there will be more information.” Snoop told Aaron in their interview.

That moment was less about celebrity and more about stake, about a man whose career spanned decades of hip-hop mythology now fumbling through a generational shift of ethics, optics and education. His participation signaled a willingness to be part of the solution but the willingness does not erase the past. It demands transparency, ongoing growth, and measurable change.

For GLAAD, for Jackson State, and for the Black queer youth who’ve had to build sanctuaries out of songs that never spoke to them, the question lingers: will this reckoning turn into sustained change? Will it inspire real advocacy in the rooms where Snoop’s voice still echoes loudest, barbershops, studios, stages, and screens?

Snoop didn’t start this conversation, but maybe, finally, he stepped into it. And for that, accountability is not a punishment; it’s a path. Because we’ve seen this pattern before— a public stumble, a carefully managed apology, and a viral redemption arc. But what the culture needs now is endurance, an unglamorous, ongoing practice of unlearning and doing better.

Love, as Snoop reminds us, is the key. But love without accountability is performance. Love without education is sentiment. Love without action is silence with good lighting. If this moment means anything, it should remind us that growth is not a press run, it’s a lifetime of choosing courage over comfort, again and again.