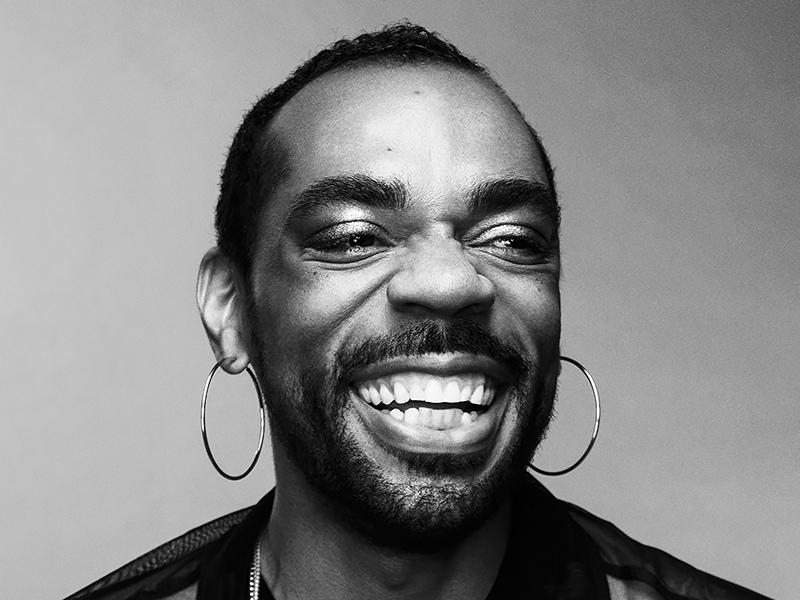

I need to start with a confession, and that is, until two years ago, I did not know the name William Dorsey Swann.

I did not know that the first documented act of queer resistance in this country did not erupt in a Greenwich Village bar in 1969, but nearly a century earlier, in a living room in Washington, D.C., hosted by a Black man born into slavery. I did not know that before Stonewall, there was Swann.

I learned his name the way so many of us learn what we were denied, through each other. It was Juneteenth, a gathering of friends marking freedom through conversation about where we’ve been, where we’re we at, and where we’re going. During a forum that drifted, as these things often do, into deeper water, my good friend Dr. Anansi Wilson stopped the room, and “learned me” something.

What he offered was not trivia. It was an expansion of my and our African American knowing, a reminder that freedom is not a static event but a lineage of refusal and joy that we inherit unevenly. That I, a Black queer person invested in liberation, had been allowed to live without this knowledge was not a personal failure, rather it was an indictment.

Whose stories are preserved as origin myths, and whose are buried as footnotes? Who gets remembered as revolutionary, and who is rendered unspeakable?

Swann matters because he represents the earliest recorded moment in American history when a queer person resisted state violence not by hiding, but by fighting back. Not metaphorically, but he did it physically and in public, in a dress.

That resistance did not wait for permission. It did not wait for whiteness to catch up. It arrived in silk and satin, carried by a formerly enslaved Black man who understood that freedom meant the right to gather, to dance, to name oneself, and to refuse erasure.

William Dorsey Swann was born on Nov. 4, 1860, in Hancock, Maryland, three years before the Emancipation Proclamation. He was enslaved by a woman named Ann Murray on a plantation in Washington County. After the Civil War, his parents purchased a farm, building a life out of land, labor, and faith that survival itself could be an act of imagination.

As a young man, Swann moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked as a hotel waiter. However, his most radical labor happened after hours. He organized secret drag balls throughout the 1880s and 1890s, often just half a mile from the White House. These were not spectacles for public consumption; they were queer sanctuaries.

Swann called himself “the Queen.” He is the first person in recorded American history to do so. Around him gathered the House of Swann, a collective of formerly enslaved men, butlers, coachmen, cooks, who dressed in cream satin and silk, who danced, who laughed, who refused the narrow futures assigned to them.

These gatherings were not frivolous; they were very dangerous. And on April 12, 1888, danger arrived at the door.

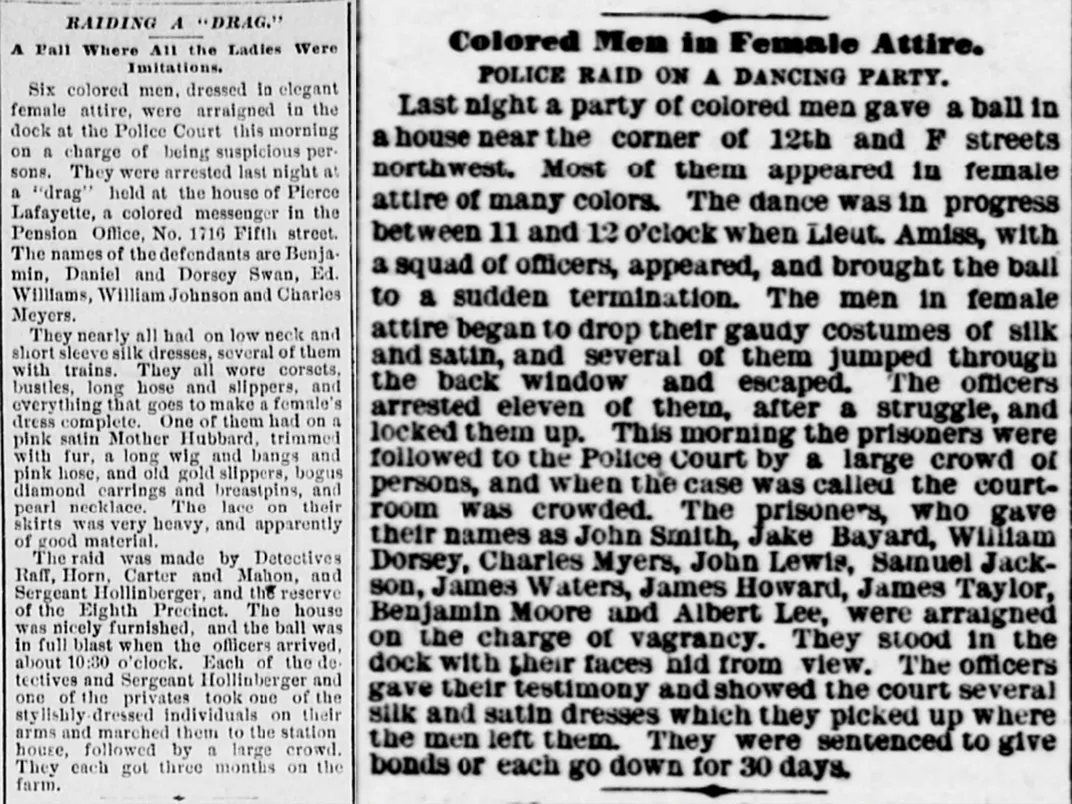

That night, police raided a house on L Street in Northwest Washington, D.C., bursting into one of Swann’s gatherings. The Washington Post headline the next day read: “Negro Dive Raided. Thirteen Black Men Dressed as Women Surprised at Supper and Arrested.”

When officers ordered the guests to disperse, Swann did not comply. According to accounts, he told the lieutenant, “You is no gentleman.” When they moved to arrest him, Swann fought back. A brawl ensued. His cream-colored satin gown was torn to shreds.

A Black, formerly enslaved, queer man physically resisting police in a dress in 1888 is not a scandal, baby, it is a rebellion.

Historian Channing Gerard Joseph identifies this moment as one of the first known instances of violent resistance to queer oppression in American history. It predates Stonewall by 81 years. And yet, it is rarely named as such.

We do not call Nat Turner’s revolt a disturbance. We do not describe Denmark Vesey’s plot as a misunderstanding. We understand those moments as what they were, refusals to accept a system designed to crush the human spirit. Swann deserves the same clarity.

What happened on L Street was not a riot, but it was a rebellion, not with bricks, but with bodies. A declaration that joy, too, was worth defending. That freedom could wear a gown. That resistance could look like a party and still be deadly serious.

And once you know Swann’s name, once you see him standing there in torn satin, refusing to yield, the story of queer resistance in America can never begin where we were told it did. And it began with a queen who learned himself free, and made room for the rest of us to follow.

Swann’s resistance did not end with bruises or a torn gown.

In 1896, years after the L Street raid, Swann was convicted of “keeping a disorderly house,” a charge routinely used to criminalize Black social life and queer gathering. The accusation was a lie thinly dressed as law. What was named as a disorder was simply joy beyond surveillance. For this, Swann was sentenced to 10 months in jail, later recorded as 300 days.

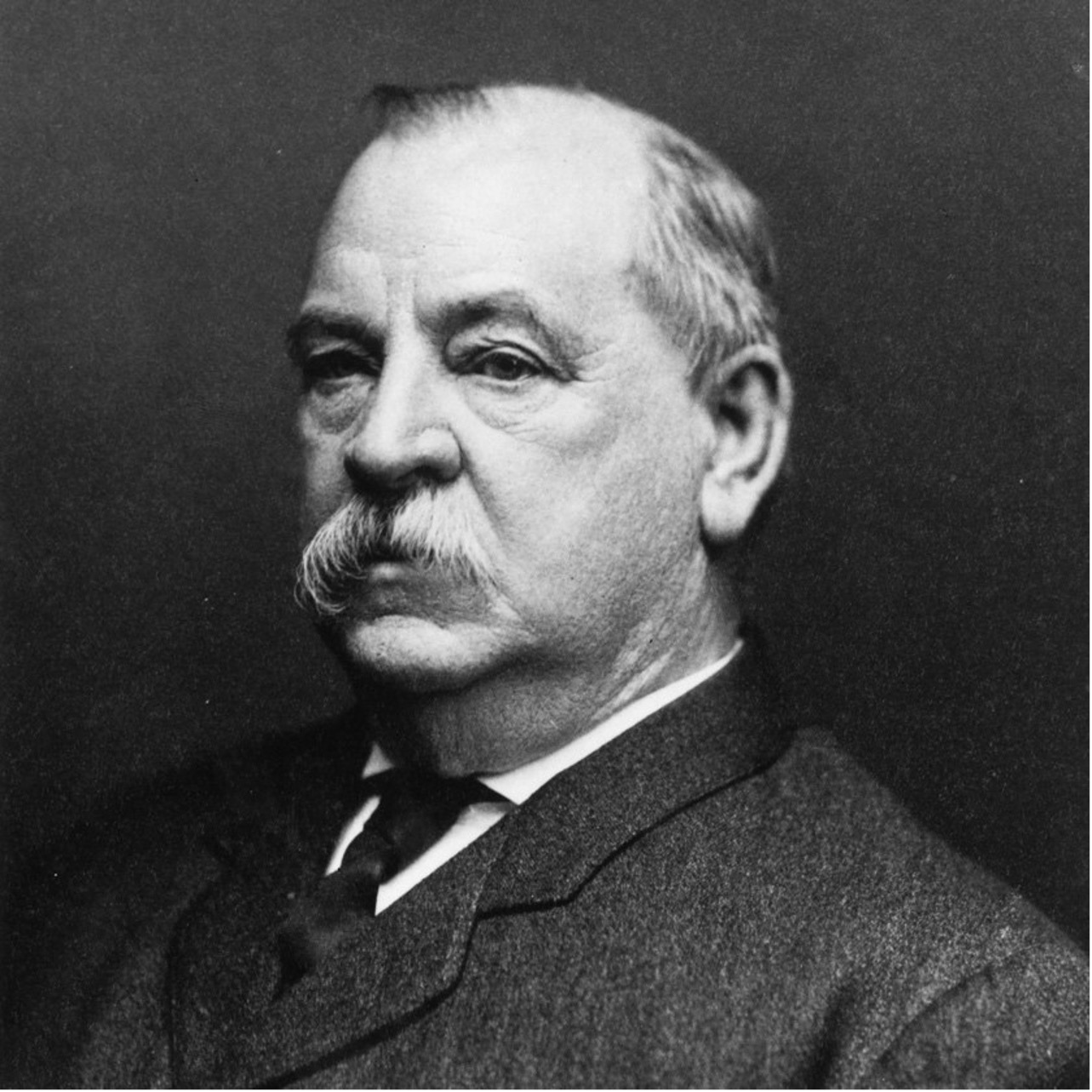

Three months into his sentence, Swann did something unprecedented. He petitioned the president of the United States for a pardon.

The document, now housed in the National Archives, marks the first known instance of an American using legal and political channels to defend the right of LGBTQ people to gather openly. Swann did not plead ignorance. He did not apologize for who he was. He stood on business and demanded recognition.

That the president, Grover Cleveland, denied the petition does not diminish its significance. A Black man born enslaved, barely a generation removed from legal nonexistence, asserted that the state had wronged him and that he was entitled to redress; it was not naïveté, but it proved to be a bold strategy.

Swann’s petition belongs to a long Black tradition of confronting power on its own terms. It sits in lineage with Frederick Douglass demanding citizenship, with Ida B. Wells exposing the lie of justice, and with the NAACP building a legal strategy brick by brick. The lesson is and was clear. Which is that resistance does not wear only one face; sometimes it throws a punch, and sometimes it files paperwork. And we would be wise to remember that both are acts of imagination.

And yet, Swann disappeared.

For nearly a century, his story lay buried in police records, newspaper archives, and pardon files no one thought to read as liberation texts. Even as LGBTQ history gained visibility, even as Stonewall hardened into origin myth, Swann remained unnamed.

It was not until 2005 that historian Channing Gerard Joseph stumbled across Swann while researching at Columbia University. What he found unsettled the established timeline. Even prominent gay historians had not known about Swann, and we now know that the absence was not accidental.

Joseph’s forthcoming book, House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens, which will be released on February 19, 2026, restores what was deliberately lost. And that loss matters. We know that erasure is not neutral. It is a form of violence that disciplines memory, narrowing the imagination of what resistance has looked like and who has been allowed to lead it.

What does it mean that Stonewall is treated as the beginning when Swann’s rebellion came 81 years earlier? Who benefits from an LGBTQ history that starts in 1969 and centers whiteness as awakening? What futures are foreclosed when Black queer ancestors are written out of both Black history and queer history?

Recovery is repair.

Swann did not leave behind a footnote. He left a blueprint.

The House of Swann established a structure we now recognize instantly, chosen family, communal gathering, performance as survival, joy as defiance. The cakewalk dances held at Swann’s balls, rooted in enslaved communities’ mocking of plantation owners, evolved over generations into the performance traditions that shape ballroom culture today.

Swann’s brother, Daniel J. Swann, continued hosting drag gatherings after William retired, providing costumes for Washington, D.C.’s drag community until his death in 1954. This is not metaphorical lineage; it is direct transmission.

That line stretches forward to Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and the Black and brown trans women who stood at the front of Stonewall. The Stonewall Uprising did not invent queer resistance; it inherited it from ancestors like William Dorsey Swann.

To say this is not to diminish Stonewall, but to place it correctly. Stonewall was not the beginning. It was a continuation. It was a relay baton passed hand to hand, gown to gown.

Swann’s life insists on relevance.

His story embodies what Audre Lorde called the transformation of silence into language and action. In an era defined by anti-trans legislation, drag bans, book censorship, and the systematic erasure of queer history, naming Swann is itself an act of love.

His existence sits at the intersections still under attack; Blackness, queerness, gender nonconformity, poverty, and the unfinished afterlife of enslavement. Swann teaches us that freedom is not only about survival, but about pleasure, assembly, and refusal. About claiming space in a world that insists you do not belong.

When lawmakers target drag performances, when schools are forbidden from teaching our histories, when queer joy is framed as a threat, Swann stands as a rebuke, and his cream satin gown becomes an argument. Moreover, his defiance becomes instruction.

To tell his story is to refuse the narrowing of our past and, by extension, the narrowing of our future.

I return, again, to gratitude.

To my beloved friend, Dr. Anansi Wilson, who “learned me” what I should have been taught long ago. To the elders, scholars, and community historians who understand that freedom is not self-executing but rather how it must be carried and spoken aloud.

Swann reminds us that freedom is not merely a legal status. It is the ability to be fully who you are in the presence of others who see you clearly. It is the right to gather, dance, and name yourself without apology.

Learn William Dorsey Swann’s name and speak it. Be sure to teach it to someone who does not yet know it. Let it complicate the stories we have been handed, and let it expand our imagination of what resistance is.

Swann was a queen. He named himself so. And in the naming, he made room for you and me.

The first act of queer resistance in America was not a riot; it was a party. And the host was a Black man in a cream satin gown who refused to let them shut it down.

Citations

Primary Sources

Currie, Netisha. “William Dorsey Swann, the Queen of Drag.” Rediscovering Black History, National Archives, June 29, 2020. https://rediscovering-black-history.blogs.archives.gov/2020/06/29/william-dorsey-swann-the-queen-of-drag/

Joseph, Channing Gerard. “The First Drag Queen Was a Former Slave.” The Nation, Jan. 31, 2020. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/drag-queen-slave-ball/

Joseph, Channing Gerard. “The First Drag Queen.” The American Academy in Berlin, Dec. 3, 2021. https://www.americanacademy.de/the-first-drag-queen/

Secondary Sources:

“William Dorsey Swann.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Dorsey_Swann

“William Dorsey Swann: The First ‘Queen of Drag.'” American Masters, PBS, Jan. 24, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/william-dorsey-swann-from-enslaved-to-queen/18722/

Franz, Meilan Solly. “William Dorsey Swann, the First Self-Proclaimed Drag Queen, Was a Formerly Enslaved Man.” Smithsonian Magazine, June 23, 2023. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-first-self-proclaimed-drag-queen-was-a-formerly-enslaved-man-180982311/

Morgan, Marjorie. “From Slavery to Voguing: The House of Swann.” National Museums Liverpool. https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/slavery-voguing-house-of-swann

“William Dorsey Swann: From Slavery to Queer Freedom in 1880s as America’s First Drag Queen.” Q Spirit, April 11, 2025. https://qspirit.net/william-dorsey-swann-queer/

Forthcoming Book:

Joseph, Channing Gerard. “House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens — And Changed the World.” Crown/Penguin Random House (North America) and Picador/Macmillan (U.K.), forthcoming Feb. 19, 2026.

Historical Newspaper Sources (Referenced in Secondary Sources)

The Washington Post, April 13, 1888 — “Negro Dive Raided. Thirteen Black Men Dressed as Women Surprised at Supper and Arrested”

The National Republican (Washington, D.C.), April 1888 — Coverage of the raid

The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), coverage of the 1887 and 1888 raids

Archival Source

Pardon Case Files, Record Group 204, National Archives, College Park, Maryland — William Dorsey Swann’s petition to President Grover Cleveland (1896)